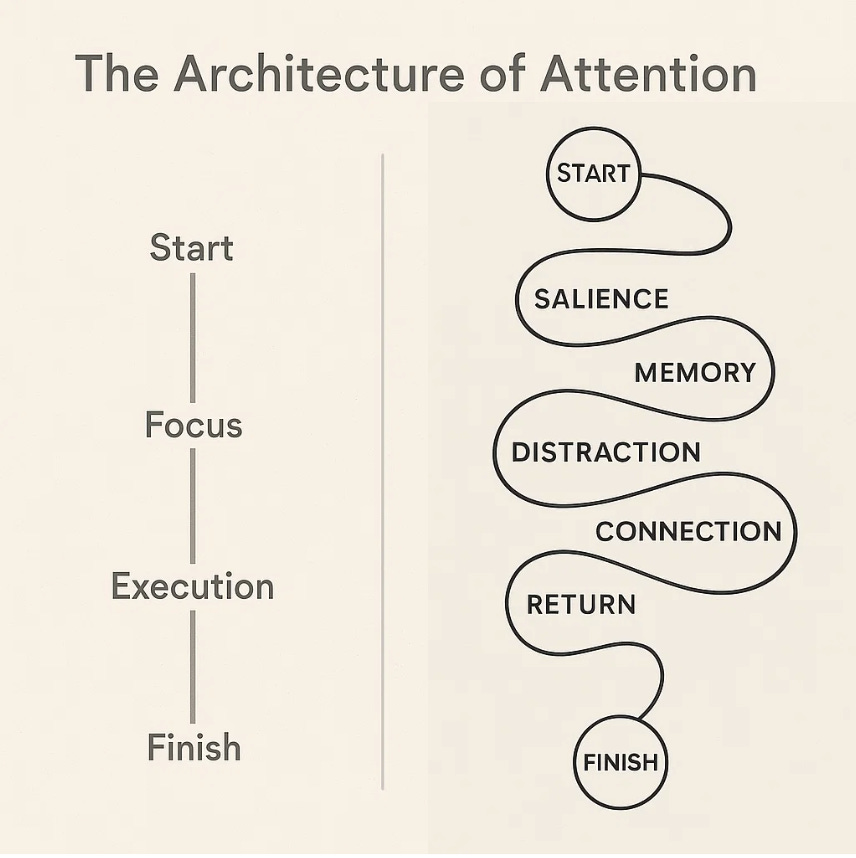

The Architecture of Attention

ADD, Holothysis, and the Shape of Thinking to Come (Holothysis 6)

Introduction: The Hidden Intelligence in Attention That Won’t Hold Still

Attention Deficit Disorder—now classified under the broader ADHD umbrella—has long been described in clinical terms: inconsistent focus, impulsivity, disorganization. But these descriptors may overstate dysfunction. They may instead reflect a form of cognitive variation poorly matched to the attentional demands of modern education and employment. What we often pathologize may be nothing more—or less—than a misalignment between mind and milieu. This article explores an alternate view of what we’ve come to call ADD—not as disorder, but as divergence. Attentional variability, exploratory drive, and associative recall are not signs of failure. They are signs of a mind adapted to a different ecology: one in which movement, novelty, and loose coherence were not just tolerated, but required.

This article explores an alternate view of what we’ve come to call ADD—not as disorder, but as divergence. Attentional variability, exploratory drive, and associative recall are not signs of failure. They are signs of a mind adapted to a different ecology: one in which movement, novelty, and loose coherence were not just tolerated, but required.

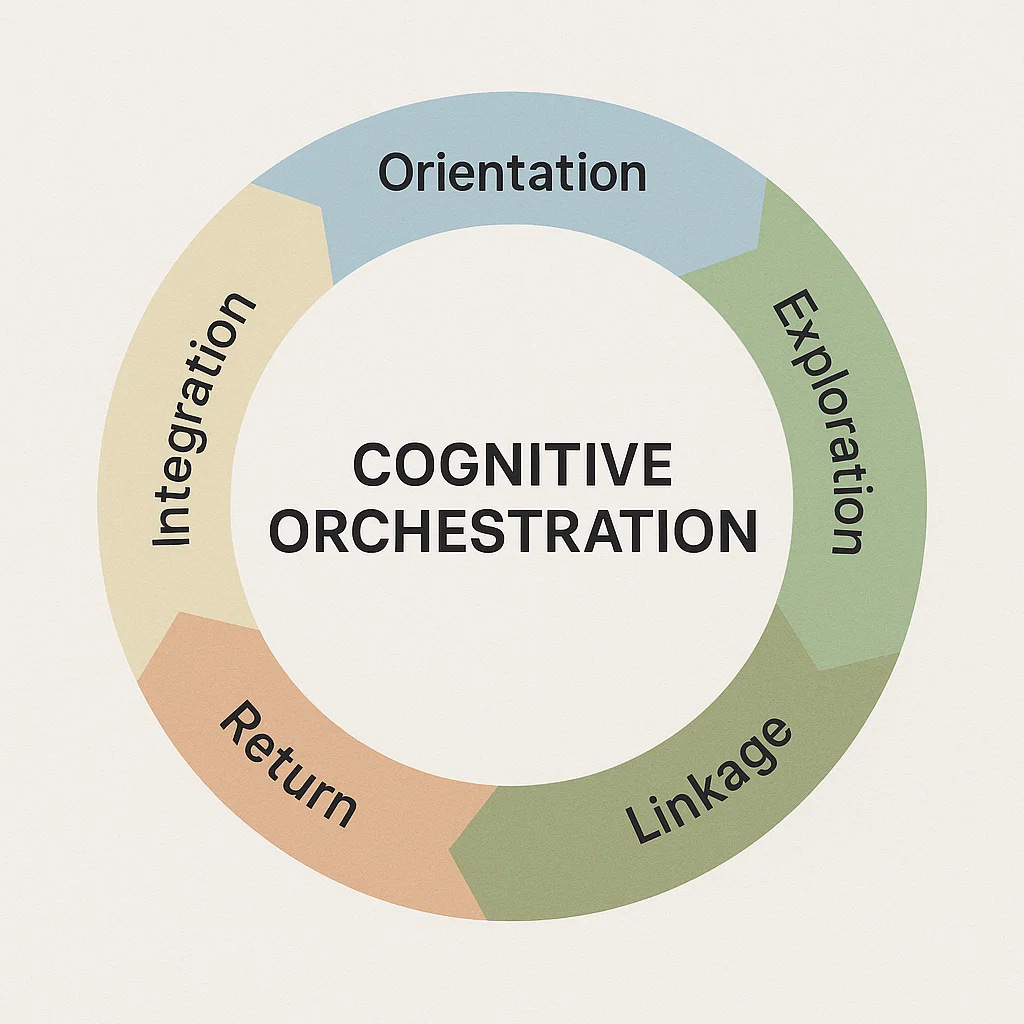

Holothysis is a name I’ve given to a particular kind of cognitive orchestration. It doesn’t describe a single trait or network, but the way multiple systems—reflection, salience detection, executive regulation—interact in motion. Some of that motion is biologically shaped. Some is learned. Some only emerges when the environment permits return.

By return, I don’t mean resuming a task. I mean the ability to re-enter a line of thought or orientation after the attention has moved elsewhere—sometimes far. In ADD-patterned cognition, the path from beginning to end may not be direct. What looks like delay or derailment may in fact be an extended arc—one that completes only if the conditions allow it. Return is not recovery. It’s resolution. It’s what allows disparate insights to cohere. And when it’s supported, the thinking becomes visible as thinking—not deviation.

This may be why I tend to hold belief as both committed and tentative. Not because I doubt what I see, but because the full arc of attention hasn't yet closed. Coherence takes time. Return needs space.

When Attention Was Adaptive

A fixed-focus mind could miss a signal on the wind. The twitch of a branch, the glimpse of movement in peripheral vision, the smell of rot near an unseen carcass would have been part of the vital data stream. The inattentive daydreamer of today might have been the vigilant sentinel of another age—attuned to patterns in flux, scanning, and open to what signals were available to be received. In this landscape, the fixated would have been the distracted: unable to map threats and resources in parallel, across time and terrain.

What we now call impulsive or unfocused behavior might once have been understood differently. In many ancestral contexts, the tendency to shift, stray, or explore wasn’t marginal—it was recognizable, and sometimes cultivated. These traits didn’t define the group, but they had their place within it. The movement away from familiar paths—cognitive or physical—led to new water, novel terrain, alternate routes. In times of migration or famine, these minds might have been the vanguard. In times of plenty, they expanded the edge.

Associative recall—the rapid, layered linking of information across contexts—made such exploration meaningful. Who better able to notice a mushroom and recall the shadowed tree beneath which it grows? To smell the soil and remember last year’s flood? To link cloud shape to danger?

None of this implies superiority. But it does suggest that what we now label disordered may be less a failure of cognition than a failure of alignment. The modern mind was not built anew. It still carries the logic of the wild—leaving some wilder minds preoccupied by sporadic sounds, stray body language, or the vivid colors strewn haphazardly across classroom walls. This does not negate the demands of the present, but it may help us widen the lens through which we understand learning—and the range of minds that have always done it differently.

How Cognition Evolved to Move

Foraging cognition—especially as modeled by optimal foraging theory (Stephens & Krebs, 1986)—describes a strategic tension between exploring new resource options and exploiting known ones. In unstable environments, this balance mattered deeply. Individuals drawn toward novelty might have been the ones who found richer patches of food, new migration routes, or safer shelter—while others kept harvesting a supply that was already running out. Exploration carried risk, but so did staying put.

This logic has since been substantiated by cognitive and behavioral study (Rosati, 2017). Minds characterized by attentional variability—one of the core traits associated with ADD—are especially attuned to change. Rather than filtering for consistency, these minds register shifts. They track movement at the edges, scan for weak signals, and remain open to new cues even while engaged in a current task. In foraging terms, they are biased toward exploration. And while that bias can appear as distraction in structured environments, it may reflect an attentional strategy evolved for dynamic landscapes, not static routines.

Remembering where something was would only get you so far. The conditions that led to its return—rainfall, wind, heat, decay—had to be tracked as well. Associative recall gave shape to those patterns. It stitched together experience across time and terrain, forming mental maps not just of place, but of sequence and recurrence. A certain fruit after a certain kind of storm. A predator's return with the east wind. These weren’t isolated memories. They were predictions built from fragments—models of when to move, where to wait, what to notice.

These traits—attentional variability, exploratory drive, and associative recall—don’t cohere into a single ideal. But they form a recognizable stance: a cognitive posture adapted to motion, uncertainty, and pattern-rich environments. In the context of ancestral survival, they made sense. In the context of modern education or employment, they often don’t. What was once a mode of orientation becomes a source of friction. Not because it is broken, but because the terrain has changed (for now).

Delayed Coordination

In people with ADD, the networks responsible for attention and task completion operate on a different timeline. These networks are not faulty. They are specialized systems—each with its own role in processing experience—and they must coordinate in order for thought to become organized action. The Default Mode Network (DMN) supports internal simulation: memory, imagination, and reflective thinking. The Salience Network (SN) monitors the internal and external environment to detect what is important enough to engage. The Executive Control Network (ECN) holds attention, sequences tasks, and moves thinking toward completion.

In many minds, these systems switch fluidly. The SN flags something as relevant. The ECN redirects attention. The DMN quiets when task demands increase. In ADD-patterned cognition, this switching is often delayed or misaligned. The DMN may remain active longer than needed. The SN may flag too many inputs or fail to distinguish what matters. The ECN may struggle to engage—or engage too late—when the other systems are already pulling in multiple directions.

This desynchronization leads to delayed action. Not because the person is confused or careless, but because the brain is still resolving how to proceed. It is still collecting input. The system hasn’t stabilized yet.

This kind of attention tends to take longer paths. It connects more inputs before it settles. It is slower to begin and slower to complete, especially without structure. But it is not empty. It is doing work.

External supports—clear steps, visual cues, time boundaries—can help this kind of attention stabilize. With the right support, the person can follow through. This is what we refer to as “return”: not resuming a task that was interrupted, but re-entering a line of thought that was still forming. Not because attention was lost, but because it hadn’t yet resolved.

Sometimes return is supported by meaning. A conversation, for example, may motivate completion because the speaker wants to be understood. They may seem to take a tangent, but if given space, they circle back. The detour adds texture to the idea. In other cases, the task itself holds the person: packing for a trip may be nonlinear, but the urgency of departure forces a resolution. The deadline becomes the structure.

Holothysis is the name for this kind of coordination—how memory, attention, salience, and control work together in motion. The pattern of that motion varies from person to person, and often diverges significantly in neurodivergent minds.

There are times when I recognize that my own thinking takes longer to resolve, or feels more wordy than it needs to be. But there are also times when a more direct expression of an idea—especially when someone tries to simplify a point I’m making—lands as a plot without the structure. Like saying Moby Dick is about a man hunting a whale. It’s not wrong. But it’s not really true either. The arc of the thought matters. So does the movement inside it.

Modern Friction, Possible Fit

A neurodivergent attentional stance falters when it can’t find traction—when the systems it moves through behave like water pipes, built to deliver force in a single vector, without any allowance to traverse laterally. That model prizes speed and efficiency. But of course, a shorter distance also covers less ground. Not every journey merits wandering, but some do. And no orchestration—no one’s holothytic cognition1 —can thrive without meeting a baseline threshold of executive stability. The mind still needs an ECN capable of holding shape, selecting purpose, and bringing work to completion.

What needs to be recognized is that with the right supports—strategies, routines, feedback loops—the tendencies of an ADD holothytic pattern can find coherence. And when it does, the stance it offers may meet the demands of a functional ECN while preserving the perceptual openness and associative mobility that neurodivergence often brings. These traits show up not only in invention or insight, but in how a person navigates complexity—how they sense drift in a conversation, shift orientation under pressure, or connect ideas others leave unlinked.

It is important not to conflate the fact that these minds are not ordinary with the idea that they are extraordinary. The point here is not to elevate, but to clarify: the stance they take toward information is different.

With enough stability to sustain action—and enough room to move—this orchestration can offer something distinctly useful to ordinary life. It can hold the pattern even as the path narrows. And it can stay the course while noticing surroundings, widening the path to accommodate more travelers and the wide variety of ideas they bring in their baggage.

Scaffolding the Loop

The cognitive patterns explored so far—especially those associated with ADD—are often most visible when a task requires sustained focus, timely execution, or inhibition of drift. The difficulty isn't that these minds can't think clearly, or that they lack purpose. It's that the systems built to hold purpose—those that initiate, sequence, and complete—are more easily disrupted.

This disruption doesn’t originate in a single source. Sometimes it’s the salience network responding too frequently. Sometimes the default mode network doesn’t quiet when it should. The executive network is still present, but its ability to hold the field can weaken when other systems pull more strongly or more often. These aren’t deficiencies in cognition itself. They’re signs of an attentional orchestration that remains open to redirection, even when closure is needed.

What’s called executive dysfunction is often a mismatch between that orchestration and the forms of performance expected by schools, employers, and bureaucracies—systems that reward steadiness, punctuality, and adherence to structure. In those contexts, attentional movement becomes friction. And for many, completing a task means fighting the very stance that supports their insight, perception, or adaptability.

Stabilization is possible, but it rarely comes from the inside alone. Strategies help: visual plans, reminders, stepwise routines. Increasingly, so do digital tools. Some track tasks. Others break work into manageable steps. Some anticipate overload and adjust accordingly. These tools don’t override cognition—they act more like ambassadors for the executive network, lobbying for direction and follow-through in a system that otherwise listens more readily to signal, story, or surprise. They intervene when internal control falters, often in the same moments salience pulls attention elsewhere. Rather than suppressing drift, they help make return possible.

Holothysis doesn’t require control in the narrow sense. But it does require enough executive strength to support motion with purpose. For minds shaped by attentional divergence, that kind of coherence becomes possible when structure is stable and scaffolds hold. Once that happens—once the ECN is assertive enough to hold shape without closing possibility—the pattern we’ve been tracing begins to look less like compensation and more like alignment. What it offers is well adapted to environments that demand presence, range, and responsiveness in real time. Not just to finish a task, but to register what's emerging, recombine what's available, and respond to what wasn't predicted. In that context, attentional variability, exploratory drive, and associative recall may suddenly become capacities to build around.

Teaching Motion, Holding Return

Neither distraction nor restlessness is a diagnosis. Sitting still too long, sleeping too little, feeling unsafe, undernourished, or overwhelmed—each can degrade executive functioning. All of these can seemingly present as ADD or ADHD, and so all should be investigated before any attempt to diagnose ADD is attempted. ADD is something truly different in terms of cognitive orchestration and needs to be dealt with as such.

What distinguishes ADD-patterned cognition is not the presence of friction, but the pattern of motion beneath it. A person with ADD does not merely struggle to focus—they struggle to hold focus because salience interrupts direction. Associations emerge, attention shifts, stories begin. The mind moves not randomly, but responsively—though often without structure. This is not an absence of discipline. It is an orchestration shaped for exploration, not suppression.

I first came to education through a mentorship program that had been developed in Latin America by an organization that was founded around the same time Freire was holding culture circles and teaching literacy in 60 days to villagers in Brazil. It wasn’t part of any formal academic institution. It operated across homes, neighborhoods, and youth groups—focused more on accompaniment and reflection than instruction. I didn’t know the name Paulo Freire then, but when I read Pedagogy of the Oppressed in graduate school, I recognized the structure. His voice felt familiar—not in language, but in rhythm, in moral orientation. Then I read Dewey, and heard the logic of experience, which echoed the same framework: learning as engagement, transformation, and return.

Later I found Miles Horton and the Highlander Institute. He wasn’t a theorist in the same way, but he built the conditions for civic learning—spaces where people learned to think and act with others. The resonance wasn’t just conceptual. It was spatial. I had worked at Teachers College the summer after high school, living in university housing with my mother. Every day, I walked past Union Theological Seminary. I found out much later that Dewey helped found Teachers College, and that both Freire’s mentor and Horton had studied at Union. For a time, the ideas that shaped my entire orientation to education were being formed within two blocks of each other. It wasn’t a coincidence. It was a pattern. I hadn’t followed it to write something profound. I followed it because the attention wouldn't let go.

This is what holothytic cognition can look like: not a straight line from prompt to product, but a dynamic, layered unfolding—where the value of attention is often only visible in hindsight.

A learning environment that recognizes this kind of movement will look different. Not chaotic, not “creative” for its own sake, but designed for orientation, return, and recombination. It might ask students to track how their thinking shifts during a task. It might allow for multiple modes of entry—textual, visual, spatial, relational. It might reward pattern construction before completion. And it would not confuse stillness with learning, or task completion with understanding.

This is where the pedagogy of presence comes in. Presence means being attuned to how cognition is moving—not just whether it is complying. It means watching the trajectory of attention, naming its pivots, and helping learners return—not by snapping them back, but by showing them how to trace their way through.

Presence is not permissiveness. It is orchestration, held from the outside, until the learner can hold it from within.

And if we can learn to teach this way—not just to tolerate this kind of thinking, but to structure for it—then we are no longer just supporting a neurodivergent profile. We are training a cognitive stance that may be increasingly well-suited to the kind of learning, work, and adaptation the future will require.

That’s what comes next.

Orchestration in a Changing Cognitive Ecology

We have spent decades trying to get certain minds to perform in systems that were not built with them in mind. Systems that equate intelligence with focus, consistency, and completion. Systems that measure cognitive capacity by how well a person suppresses distraction and delivers output on schedule. These systems were not designed to reward exploration, recombination, or drift that precedes insight. And so, minds that move that way have struggled—not because they lack intelligence, but because the structure wasn’t built to let that intelligence cohere.

That structure is beginning to shift.

As AI systems take up more of the procedural and managerial work that once relied on internal executive function, the pressure on human cognition is changing. What becomes valuable is not the ability to maintain linear control, but to interpret, integrate, and reorient in real time. The kind of thinking that thrives in ambiguity. The kind that tracks patterns across systems. The kind that moves, then returns. This isn’t a speculative future. It’s already visible—in the work that requires adaptation, synthesis, and decision-making under changing conditions.

ADD does not offer a better mind. It offers a more exposed one. What we’ve called dysfunction may in some cases be a form of cognition that was never scaffolded long enough to complete its loop. A form that moves early, notices the wrong detail, asks the off-topic question, connects what wasn’t assigned to be connected. But when the right support is there—enough structure to stabilize, enough freedom to move—this form can cohere. Not perfectly. But enough to show us something real.

We’re not ready to be too bold in our characterization of Holothysis. But if it is the orchestration of the neurological networks responsible for different aspects of thought—if the networks are the instruments of cognition, and Holothysis is the layer that arranges their interaction—then I begin to wonder whether this is actually what we mean when we talk about thinking. Not the content. Not the precision. But the act of coordinating parts that don’t belong to a single system. Some of that orchestration is biologically shaped. Some of it is environmental. Some is trained. All of it is affected by what we’ve learned, formally or informally, and by what support structures are available in real time.

The conductor isn’t the most important part of the orchestra. You cannot conduct if no one is playing. Leadership requires followership. Teaching requires learning. And Holothysis is not more important than executive function. But it is different. And because it is distributed across all cognitive systems—and only becomes visible through their motion—it may offer the clearest picture we have of what thinking actually is.

Not a Conclusion, But a Pattern

We began with ADD not to glorify it, but to expose what it reveals. Neurodivergence, in this case, is a way of seeing variation in how cognition is orchestrated—how networks interact, how attention moves, how coherence is built. We did not argue that difference is always a strength, or that it has been deliberately suppressed. We argued that what looks like dysfunction may in some cases be a different form of motion—one that only becomes legible when the environment makes return possible.

Being neurodivergent in a world built for structure is not a secret power. It is often a life of constant translation, suppression, and missed legitimacy. If you can’t be on time, complete forms, or stay quiet when it’s expected, the world will treat you accordingly. That isn’t a conspiracy. That’s what institutions do. But we’ve also shown that once scaffolds are in place—especially those now emerging through adaptive AI—those same minds can stabilize long enough to let their associative, variable, and exploratory functions do useful work.

This does not mean that people with ADD are better suited for the future. It means that the orchestration pattern visible in ADD, once stabilized, may resemble the kind of thinking that will be increasingly necessary. And if that’s true, then what we’ve been trying to suppress or rehabilitate may instead be a clue. A pattern that can be cultivated—not just in the few, but in the many. We’ve spent years training neurodivergent minds to get by in the world we had. We may now need to train the rest of us to move more like them in the world that’s coming.

Of course, at this early stage in exploring Holothysis, I can only say that I’ve taken a few steps beyond what began as a hunch—something tugging at the corner of my mind that I recognized from prior experience as the kind of tug that usually leads to a pattern. One that hadn’t yet taken shape, or that might be understood more clearly if named in slightly different terms. I’m no expert in neuroscience or psychology, and I don’t mind being wrong. If this concept doesn’t yield enough fruit to justify the digging, I’ll move on and look for resources elsewhere. After all, I’ve got ADD.

- Dox

For a deeper dive into holothysis, please see A Philosophy of Mind That Doesn't Fragment the Self