What Do You Want for Them?

Rebuilding the Educational Compact in the Age of AI

Authors Note:

This is a first attempt to say something structurally honest about the disruption AI brings to education—not in terms of cheating, but in terms of disconnection. The questions below aren’t theoretical. They’re urgent. And they don’t just apply to the classroom. They apply to any place we ask someone to become more than what they were.

“What do you want from students?”

only becomes clear

once you’ve answered:

“What do you want for them?”

I. The Collapse of Pedagogical Intuition

There’s a lot being said about AI and education right now. Declarations, predictions, policy alarms, counter-alarms. Everyone seems to agree that something has changed. Some believe everything has. I don’t disagree—but I’m not sure the change is as clean or as new as it’s being made out to be.

This may be a moment of disruption. But if it is, it’s not the first. And it might not even be the sharpest. AI presents real challenges to how we think about pedagogy, authorship, and trust—but it also exposes how much of that thinking had already become unexamined. If there is a crisis here, it may be less about the arrival of AI than about our reliance on rituals whose meaning we forgot to revalidate.

The assignment still exists. The student still exists. But the connection between the two has gone fuzzy. We tend to assume that connection used to be tight and obvious. I’m willing to give that benefit of the doubt—if only because the alternatives are either cynicism or amnesia.

AI is now making visible a question we’ve deferred. A question that was always embedded in our practice but rarely named aloud. What do you actually want from your students? What were you hoping would happen when you assigned that project, that reading, that paper? What kind of transformation were you trying to set in motion?

The harder truth is that this question has two parts, and we’re mostly struggling with the second one. You’re probably already wrestling with it. What do you want from students now that AI can draft, summarize, translate, and analyze better than most of them—and sometimes better than you? What do you do with that assignment you used to trust, now that its completion no longer guarantees any actual encounter with the material?

Some are trying to tighten the net—ban the tools, lock the browsers, watch the prompts. But surveillance is expensive, and moralizing is usually hollow. More importantly, neither of these responses actually reattaches the task to the learner. The loop is broken. You can’t extract evidence of growth if the task no longer provokes any.

So I’d suggest backing up—past the debate over cheating, past the impulse to monitor or punish, and even past the question of what you want from your students. Because that question only becomes legible once you’ve answered a deeper one: what do you want for them?

That’s the real prompt. The one most of us were never asked to write a response to. You may have known at one point what you wanted your students to become—what capacities you were hoping to unlock, what transformations you were hoping to ignite. You may even still know. But the system didn’t require you to say it out loud. Until now.

[I created my own answer, but you’ll have to skip to the end if you want my answer. And my answers are always full of conviction and completely tentative.]

II. The AI Disruption Is Not About Cheating

We can stop pretending the real issue is dishonesty. AI didn’t invent cheating—it just made the shortcut indistinguishable from the output. The deeper problem is that we’re no longer sure what we’re measuring. The tasks we once assigned to develop thinking are now easily completed without thinking at all. So the assignment still exists, and the student still submits something—but the loop is broken.

I don’t always know what a biology lab is supposed to cultivate. I’m not certain what a poetry seminar should leave students with. I have instincts about what a creative writing course can unlock, and I carry some polysyllabic convictions about what a political science or education graduate student should be able to synthesize. But I also want something basic. I want students to label a blank map. I want them to know some things that might be forgotten later. I want them to have done it at least once.

I see value in the things that feel like busywork, not because I worship rigor, but because they make the moments of deep engagement feel real. Life is full of administrative labor. Most jobs are a blur of relevance and irrelevance. If we pretend the classroom should be a constant site of peak cognition, we are lying to students about the world we are preparing them for.

Still, the deeper current running beneath all of this is language. Not English. Not writing. But language as a construct, an object of study, and a condition of human continuity. I want students to engage with expanding arenas of language at increasing levels of complexity—not to be more verbal, but to become more human. Language is the chisel we use to carve out meaning. AI may be fluent, but it cannot be confused, and confusion is where thought begins.

So yes, I can’t always trust their writing anymore. But I can still make them talk. I can still test for presence. I can still ask them to stand in front of something complex and live with it out loud. Not every student will like this. Some will be terrified. But I’ve found that fear tends to shrink when competence increases. Even the shyest student becomes articulate when they actually know what they’re talking about.

That’s what I’m after now. Real-time, public, and sometimes awkward demonstrations of actual understanding. Not as punishment—but as proof. As the only kind of output that AI cannot automate. Students can show up. They can pivot. They can ask real questions. They can change their mind. That is what I want from them—because I still know what I want for them.

III. First Principles: What Was the Original Contract?

Every course is a kind of promise, even if no one called it that. It’s a structure built to produce something—some capacity, some understanding, some shift in perception. That structure may have been inherited, or imposed, or loosely held together with the wires of tradition and habit. But at some point, you made choices: what to teach, how to assess, what mattered enough to make students do it. The course always implied that the experience was worth the effort.

Now that effort is getting rerouted. Students can complete many of the tasks we assign them without passing through the experience those tasks were meant to evoke. That doesn’t mean they’re lazy or immoral. It means the tools have changed. The bridge is out.

I don’t think this is a crisis of character. I think it’s a crisis of clarity. And the only way forward is to ask a different kind of question: What was the point? What were you hoping they’d become through this practice, this reading, this experiment, this paper? What did you want for them?

It’s not a failure if you realize that the thing you once wanted no longer makes sense—or arrives through other means. There’s a lot to be learned from blacksmithing. I don’t expect many students to take a class in it. But the core learning—discipline, patience, manual cognition, transformation through heat and pressure—might still come from elsewhere. From a physics lab. From assembling furniture. From learning how to style your hair.

But not everything translates. And not everything can be automated. I still believe poetry has value. Creative writing is a way of seeing. Literature is a way of understanding reality. None of that depends on being the best writer in the room. None of that was ever just about grading performance. And if you’re teaching in those spaces, I expect you to find the new path. Because I can’t do it for you. And if you can’t do it, who will?

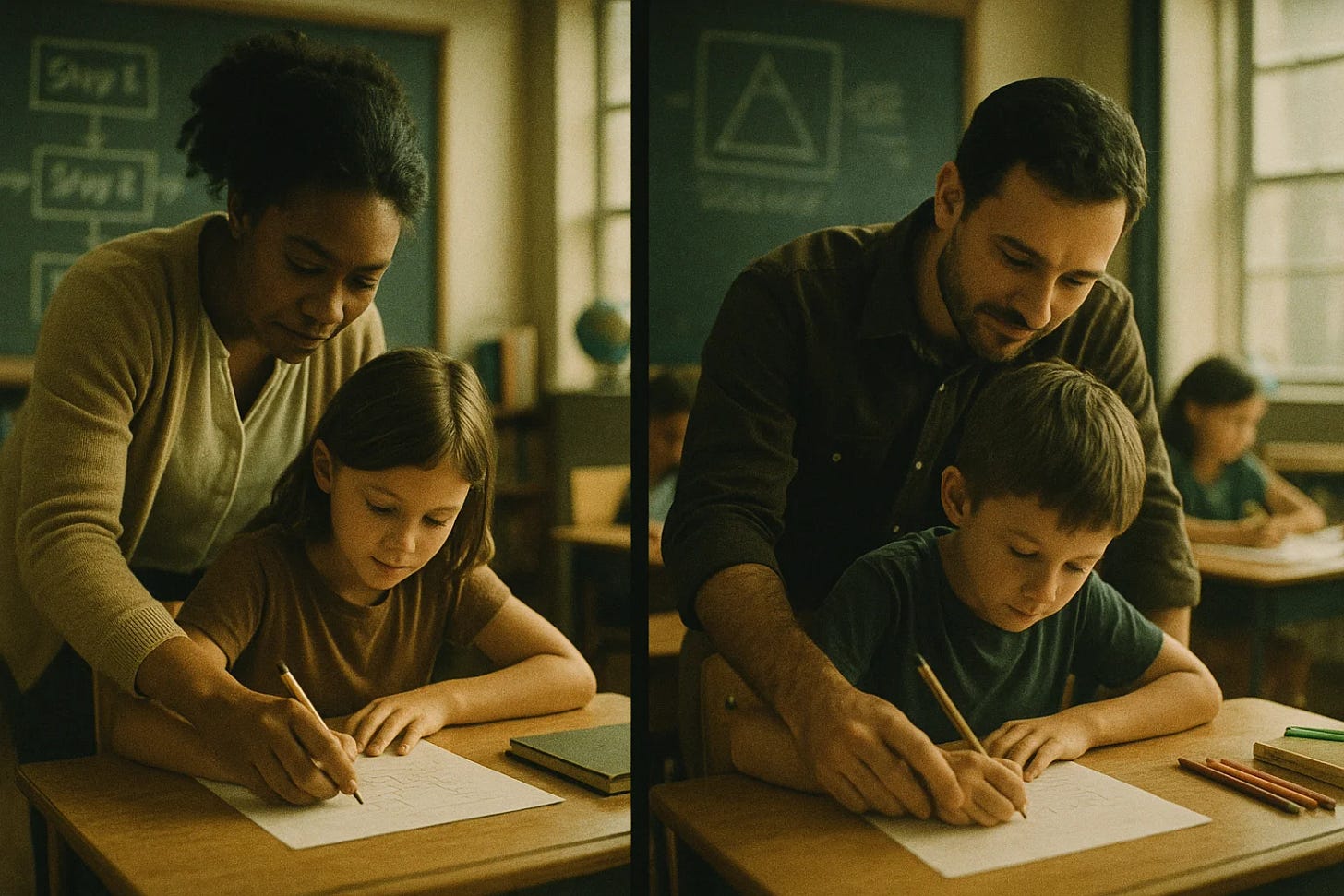

I know this much: you won’t be able to stop students from using AI. You might catch them in a final exam. You might expose them through oral engagement, through presence. But if you still want something for them, then you’ll need to help them use this tool in pursuit of that. Not as a shortcut to avoid the experience, but as a way to enter it more deeply. AI is just another instrument. The chalkboard. The pencil. The laptop. The journal. The difference now is that the instrument performs. And the question is whether that performance still tells you anything real about what the student has become.

IV. Presence as the New Epistemic Ground

If the assignments we used to trust no longer show us what students have become, we have to shift the terrain. AI can now draft, organize, revise, and polish written output faster than most students and more fluently than many educators. That doesn’t mean students no longer need to write. It means writing is no longer the clearest place to see the learning.

Real-time responsiveness is becoming the front line of education—not because it’s novel, but because it’s where human beings have always lived. Mind, body, spirit: presence is our native mode. It’s not just what AI can’t do. It’s what makes us different in the first place.

Students must learn to think with others—in time, in context, in complexity. They have to interpret ideas without prompts, carry uncertainty without collapse, and let their knowledge speak through them in the moment. This isn’t about style. It isn’t about charisma. Presence is not a performance. It’s the epistemic signature of someone who is actually there.

This will be difficult. Some students will resist. Some will panic. But even the quietest among them can rise to it if they’ve done the work. Competence precedes confidence. And presence, when it’s grounded, is not about being the loudest—it’s about being able to carry what you know across the threshold of shared reality.

I want to be clear: this is my first, tentative, and best guess at what teaching might look like in the time of this technological churn. This moment is not like past shifts. AI doesn’t just support performance—it performs. And it performs well. But as long as there is language, there is a we. As long as there is a we, it will need all of us. And as long as we are needed, it behooves all of us to learn—and to teach others—what it means to show up. It seems, at the very least, a decent place to start.

V. Why It Matters: The Civic and Professional Arc

Presence isn’t just a pedagogical strategy. It’s a civic requirement and a workplace demand. You can’t vote with a prompt. You can’t negotiate policy or lead a community meeting or sit in disagreement with someone else’s lived experience through a chatbot. AI can write the position paper. It can summarize the town hall transcript. But it cannot decide, it cannot reconcile, and it cannot care.

Civic life depends on the ability to be clear under pressure, to speak with both conviction and context, and to recognize when precision matters more than persuasion. The next generation of public actors—activists, voters, teachers, council members—will not just need information. They will need discernment, timing, and the courage to be articulate before they are certain. This is what education can still offer them—if we stop pretending that essays are proxies for participation.

The workplace will demand just as much.

And let’s be clear: this doesn’t only apply to the so-called knowledge economy. The rise of AI is driving renewed interest in the trades—plumbing, electrical, mechanical, logistical work. These are jobs that AI, for now, cannot touch. They require hands, coordination, spatial reasoning, technical discipline. They are deeply human. But they are not exempt from the need for education.

If the “cerebral” students begin to choose trades—as many are—they will thrive in those spaces too. Not because they can tighten a bolt faster, but because they can navigate uncertainty, explain their work, adjust on the fly, and lead others. The intellectual arms race doesn’t disappear in the trades. It just relocates.

That’s why presence matters there too. Clarity, adaptability, discernment, and the ability to think aloud in the company of others—these aren’t academic skills. They’re human ones. If we pretend only “school-bound” students need to develop them, we are preloading the next layer of inequality—one based not on college degrees, but on the ability to respond when the tools run out.

Collaboration is not merely a team assignment. It’s a long-term test of how well someone can contribute when the tools are shared, the conditions are shifting, and no one is entirely in control. AI might build the slide deck. It might run the numbers or pre-draft the memo. But the meeting still happens. The decision still has to be made. The client still has to be called. Someone still has to show up and know what they’re talking about.

None of this makes presence optional. It makes it urgent. The capacity to interpret context, respond fluidly, offer ideas without overconfidence, and build something in real time with other minds—these are the new high-value skills. They always mattered. But now they’re visible.

And this shift doesn’t just change what we assess. It changes the dynamics inside the room. Not every student is equally equipped to speak up. Some will feel excluded. Some will initially falter—not because they lack intelligence, but because they weren’t trained for visibility. We’ve long tried to protect students from these moments of public uncertainty, often out of compassion. And in many cases, that caution was justified.

But is it still? If presence is now a core demand of civic and professional life, then refusing to ask for it in school is no longer protective. It may be negligent. The question is no longer should we ask for presence—it’s how we do it responsibly.

We are not asking for performance. We’re not demanding charisma or fluency. We are hypothesizing—tentatively, but with purpose—that competence will crowd out celebrity, and that presence, in a truly collaborative environment, will not be a contest of dominance. The task now is to build classrooms that support emergence, not spotlight. Presence is not a vehicle for ego. It’s a structure for contribution. It is how students practice being necessary to others. And that shift will not be easy. But it might be necessary.

VI. Technicians, Experts, Educators

This is not just another shift in instructional design. It’s not another learning theory to debate, or another tool to evaluate for potential gains. This is a rupture in the logic of how education works. And the burden of response doesn’t fall on policymakers, or platforms, or AI companies. It falls on educators—because they are the only ones situated close enough to students, and wide enough in scope, to take on the challenge at scale and at depth.

We’ve never quite faced an educational problem like this. Not because it’s a crisis of cheating. Because it’s a crisis of transfer. The whole idea of an assignment was that it mapped a student’s effort to a visible result. That map is broken. The performance can now be separated from the process. The product no longer guarantees the experience.

And that puts us in Apollo 13 territory. The mission is still live. The environment has changed. The constraints are non-negotiable. And the only way forward is to redesign a human learning ecosystem using what we have left: presence, discernment, attention, dialogue, and the courage to reimagine what “school” is supposed to produce.

If P–12 education is staffed only with technicians—people who follow scripts, implement packages, and enforce compliance—then we cannot expect colleges to function with only experts. The technician-to-expert pipeline is already showing signs of failure. Students arrive with gaps that content mastery alone cannot fix. They are literate, but not oriented. They are trained, but not formed.

Colleges can house experts. That’s fine. But they can’t replace the formative work that must happen earlier. The link between early childhood and post-secondary must be rebuilt—not administratively, but epistemologically. The work of turning people into learners—into thinkers, into agents, into adults—has no clear institutional home. And yet it is more urgent now than ever.

Because those who do not become learners in this age will not just be less successful. They will become tools. Optimized. Automated. Flattened into functional compliance. The very thing we say AI threatens to do to humans—turn them into inputs—is exactly what education must now resist. But it cannot do so with outputs. Only with formation. And that is the educator’s work.

Most can perform. Only some can learn. And unless we change the conditions under which learning is cultivated and recognized, that split will define the next phase of inequality.

VII. The Rewritten Compact

We’re not finished. We’re just out of time to pretend the old structures still hold. The assignments that used to carry the weight of formation now often function as performance rituals. That’s not anyone’s fault. But it is our problem.

If presence is the only thing AI cannot do—if it is the epistemic ground of human becoming—then it must return to the center of our pedagogy. This means redesigning what we ask of students. Not to catch them, not to challenge them for sport, but to build the conditions under which real learning can be seen again. That might mean fewer essays as final products, but not fewer essays as preparation. It might mean privileging the process over the artifact. It might mean shifting the site of assessment from submission to demonstration. And it will almost certainly mean more dialogue, more responsiveness, more risk. And not just from students.

We have protected students from that kind of presence out of compassion. We have softened the demand to be visible. But if we believe real-time participation is now a condition of civic and economic life, then continuing to protect them from it may not be compassionate at all. It may be negligent. We’re not asking them to perform. We’re asking them to practice being needed. We are recognizing the need for all of them to be right here, right now—ready and able to contribute, and to be counted. Not because they’re extroverted. Not because they’re perfect. But because participation is no longer optional in a world where presence is the last working signal of human value—value that must still be rendered in human terms, for a human world.

This is not about restoring rigor. It’s about restoring reality. The classroom was never meant to be a site of personal performance. It was meant to be a shared space for reading the world together. A rehearsal for the real: where meaning is co-created, where presence is not self-expression but contribution, and where the act of learning becomes a form of showing up—for others, with others, in real time.

That’s the promise. That’s the compact.

And we don’t have to abandon the old language to keep that promise alive. We just have to speak it in a new key. What do you want for them? What do you want from them? And what kind of experience still carries the power to deliver both?

That’s the work now. That’s the assignment. And like the best ones, we may not know if it’s working until they carry it out into the world and use it to build something we can recognize—together. We won’t get the whole path right. But we can still name a first step. And right now, that may be the most important thing: to hold in our mind’s eye what we want for them, so we can begin to understand what to ask from them, and what it means to show up and do that job. Everyone can try. Everyone can help name a step. But we have to move. The compact won’t rewrite itself.

💬 If you’re an educator, administrator, policymaker, or student:

What’s one thing you still want for learners?

What’s one thing we should stop asking from them?

What’s one first step that would make a real difference right now?

You don’t need a master plan. You just need a way to begin again—with clarity.

📎 Appendix: My Answer

Earlier I wrote:

“[I created my own answer, but you’ll have to skip to the end if you want my answer. And my answers are always full of conviction and completely tentative.]"

This is that answer.

🧠 As an Educator, What I Want for Them

🧠 As Intellectuals

I want them to move beyond opinion and into the responsibility of thought.

I want them to think in slow loops—not just to argue, but to revise.

I want them to feel when something needs to be named, and when holding tension is the more honest act.

I want them to recognize meaning as a structure, not a vibe.

And I want them to join the long human project of carrying truth—imperfectly, provisionally—forward.

🌍 As Humans

I want them to become legible to themselves, not just performatively fluent in front of others.

I want them to be able to suffer well—not with fatalism, but with insight and proportion.

I want them to practice mercy where intellect alone might win them applause.

I want them to befriend uncertainty without romanticizing it.

And I want them to hold complexity without collapse.

🏘 As Parents and Community Members

I want them to develop intergenerational conscience.

I want them to know that “community” is not a vibe, but a set of obligations—material, emotional, and narrative.

I want them to be the kind of person who knows how to sit with a child asking a real question—and not look away.

I want them to be unafraid of conflict, because they’ve learned how to stay in the room after it.

🧰 As Experts

I want them to master something—but more importantly, to understand what mastery requires.

I want them to resist the false certainty of polished language, and remember that real expertise always includes doubt.

I want them to be able to build systems, not just critique them.

I want them to carry the ethical burden of precision—and to know that excellence means something different when it touches real lives.

🔁 As Learners

I want them to look up words they don’t already know.

I want them to remember that learning is recursive, not linear.

That it isn’t just a life phase—it’s a way of staying in relationship with the world.

I want them to learn how to ask better questions, not just perform better answers.

And above all, I want them to remain porous to the unknown.

🧷 As a Pedagogue of Presence

I want them to develop discernment—not just knowledge, but the ability to detect relevance, contradiction, precision, and shallowness in what they encounter.

I want them to cultivate holothysis—the recursive capacity to think across symbolic systems without flattening them.

I want them to be present—not performative, but responsive; capable of showing up in a room with other minds and making meaning out of mutual attention.

I want them to grapple with language not just as a communication tool, but as an instrument for carving the edges of reality.

I want them to have orientation—to know how to proceed when certainty fails, interpretation fractures, or authority misfires.

I want them to fail generatively—to metabolize error, not just recover from it.

I want them to matter to each other—to treat the classroom as a provisional commons, not a stage or a silo.

I want them to be adults.

I want them to be servants and role models and failures and wide awake.